Zoroastrianism is one of the world’s oldest known living religions and has its origins in the distant past. This religion shares a common heritage with the Vedic religion of Ancient India and Hinduism. It is thought to have taken root in Central Asia during the second millennium BCE, and from there spread south to Iran.

The sacred texts of the Zoroastrians and assembled in a body of literature called the Avesta. Composed in an ancient Iranian language, Avestan, the Avesta is made up of different texts, most of which are recited in the Zoroastrian rituals, some of them by priests only, others by both priests and laypeople.

Know about Zend-Avesta

ZEND – AVESTA, the original document of the religion of Zoroaster, still used by the Parsees as their bible and prayer-book. The name ” Zend-Avesta “ has been current in Europe since the time of Anquetil Duperron (c. 1771), but the Parsees themselves call it simply Avesta, Zend being specially employed to denote the translation and exposition of a great part of the Avesta which exists in Pahlavi.

ZEND – AVESTA, the original document of the religion of Zoroaster, still used by the Parsees as their bible and prayer-book. The name ” Zend-Avesta “ has been current in Europe since the time of Anquetil Duperron (c. 1771), but the Parsees themselves call it simply Avesta, Zend being specially employed to denote the translation and exposition of a great part of the Avesta which exists in Pahlavi.

Origin of the word Avesta

Text and translation are often spoken of together in Pahlavi books as Avistak va Zand (” Avesta and Zend “), whence – through a misunderstanding – our word Zend-Avesta. The origin and meaning of the word ” Avesta ” (or in its older form, Avistak) are alike obscure; it cannot be traced further back to the Sasanian period.

Must Read: RABBI EZEKIEL ISAAC MALEKAR : THE FACE OF JUDAISM IN DELHI

Language of the Avesta

The language of the Avesta is still frequently called Zend; but, as already implied, this is a mistake. We possess no other document written in it, and on this account modern Parsee scholars, as well as the older Pahlavi books, speak of the language and writing indifferently as Avesta. As the original home of the language can only be very doubtfully conjectured, we shall do well to follow the usage sanctioned by old custom and apply the word to both.

Although the Avesta is a work of but moderate compass (comparable, say, to the Iliad and Odyssey has taken together), there nevertheless exists no single MS. which gives it in entirety.

This circumstance alone is enough to reveal the true nature of the book: it is a composite whole, a collection of writings, as the Old Testament is.

It consists, as we shall afterward see, of the last remains of the extensive sacred literature in which the Zoroastrian faith was formerly set forth.

Parts of Avesta

As we now have it, the Avesta consists of five parts – the Yasna, the Vispered, the Vendidad, the Yashts, and the Khordah Avesta.

As we now have it, the Avesta consists of five parts – the Yasna, the Vispered, the Vendidad, the Yashts, and the Khordah Avesta.

The Yasna

The principal liturgical book of the Parsees, in 72 chapters (hait-i, ha), contains the texts that are read by the priests at the solemn Yasna (Izeshne) ceremony, or the general sacrifice in honor of all the deities. The arrangement of the chapters is purely liturgical, although their matter in part has nothing to do with the liturgical action.

The kernel of the whole book, around which the remaining portions are grouped, consists of the Gathas or ” hymns ” of Zoroaster, the oldest and most sacred portion of the entire canon. The Yasna accordingly falls into three sections of about equal length: –

(a) The introduction (chaps. 1 -27) is, for the most part, made up of long-winded, monotonous, reiterated invocations. Yet even this section includes some interesting texts, e.g. the Haoma (Horn) Yasht (9, i i) and the ancient confession of faith (12), which is of value as a document for the history of civilization.

(b) The Gathas (chaps. 28-54) contain the discourses, exhortations, and revelations of the prophet, written in a metrical style and an archaic language, different in many respects from that ordinarily used in the Avesta. As to the authenticity of these hymns, see Zoroaster. The Gathas proper, arranged according to the meters in which they are written, fall into five subdivisions (28 -34, 43-4 6, 47-5 0, 51, 53).

Between chap. 37 and chap. 43 is inserted the so-called seven-chapter Yasna (haptanghaiti), a number of small prose pieces not far behind the Gathas in antiquity.

(c) The so-called Later Yasna (A paro Yasno) (chaps. 54-72) has contents of considerable variety but consists mainly of invocations. Special mention ought to be made of the Sraosha (Srosh) Yasht (57), the prayer to fire (62), and the great liturgy for the sacrifice to divinities of the water (63-69).

Must Read: Japanese Ikigai: Art of Finding Purpose in Life

The Vispered

A minor liturgical work in 24 chapters (karde), is alike in form and substance completely dependent on the Yasna, to which it is a liturgical appendix.

Its separate chapters are interpolated in the Yasna in order to produce a modified – or expanded – Yasna ceremony. The name Vispered, meaning ” all the chiefs “ (vispe ratavo), has reference to the spiritual heads of the religion of Ormuzd, invocations to whom form the contents of the first chapter of the book.

The Vendidad

The priestly code of the Parsees, contains in 22 chapters (fargard) a kind of dualistic account of the creation (chap. 1), the legend of Yima and the golden age (chap. 2), and in the bulk of the remaining chapters the precepts of religion with regard to the cultivation of the earth, the care of useful animals, the protection of the sacred elements, such as earth, fire and water, the keeping of a man’s body from defilement, together with the requisite measures of precaution, elaborate ceremonies of purification, atonements, ecclesiastical expiations, and so forth.

These prescriptions are marked by a conscientious classification based on considerations of material, size, and number; but they lose themselves in an exaggerated casuistry.

Still, the whole of Zoroastrian legislation is subordinate to one great point of view: the war – preached without intermission – against Satan and his noxious creatures, from which the whole book derives its name; for ” Vendidad ” is a modern corruption for vi-daevo-datem – “ the antidemonic Law.”

Fargard 18 treats of the true and false priest, of the value of the house-cock, of the four paramours of the she-devil, and of unlawful lust. Fargard 19 is a fragment of the Zoroaster legend: Ahriman tempts Zoroaster; Zoroaster applies to Ormuzd for the revelation of the law, Ahriman and the devils despair, and flee down into hell. The three concluding chapters are devoted to sacerdotal medicine.

The Yasna, Vispered, and Vendidad together constitute the Avesta in the stricter sense of the word, and the reading of them appertains to the priest alone.

For liturgical purposes, the separate chapters of the Vendidad are sometimes inserted among those of the Yasna and Vispered. The reading of the Vendidad, in this case, may, when viewed according to the original intention, be taken as corresponding in some sense to the sermon, while that of the Yasna and Vispered may be said to answer to the hymns and prayers of Christian worship.

The Yashts

“Songs of praise” that is Yashts is so far as they have not been received already into the Yasna, form a collection by themselves. They contain invocations of separate Izads, or angels, number 21 in all, and are of widely divergent extent and antiquity.

The great Yashts – some nine or ten – are impressed with a higher stamp: they are cast almost throughout in a poetical mold and represent the religious poetry of the ancient Iranians. So far they may be compared to the Indian Rig-Veda.

Several of them may have been cemented together from a number of lesser poems or songs. They are a rich source of mythology and legendary history.

Side by side with full, vividly colored descriptions of the Zoroastrian deities, they frequently interweave, as episodes, stories from the old heroic fables.

The most important of all, the 19th Yasht, gives a consecutive account of the Iranian heroic saga in great broad lines, together with a prophetic presentment of the end of this world.

The Khordah Avesta

The Little Avesta comprises a collection of shorter prayers designed for all believers – the laity included – and adapted for the various occurrences of ordinary life.

In part, these brief petitions serve as convenient substitutes for the more lengthy Yashts – especially the so-called Nyaishes. Over and above the five books just enumerated, there are a considerable number of fragments from other books, e.g. the Nirangistan, as well as quotations, glosses, and glossaries.

Must Read:-Religion, Faith and Coronavirus

Must Read:-Indian Faith leaders coming together for Earth: UNEP Faith for Earth Symposium

Research: Avesta – Ancient History Encyclopedia, avesta.org

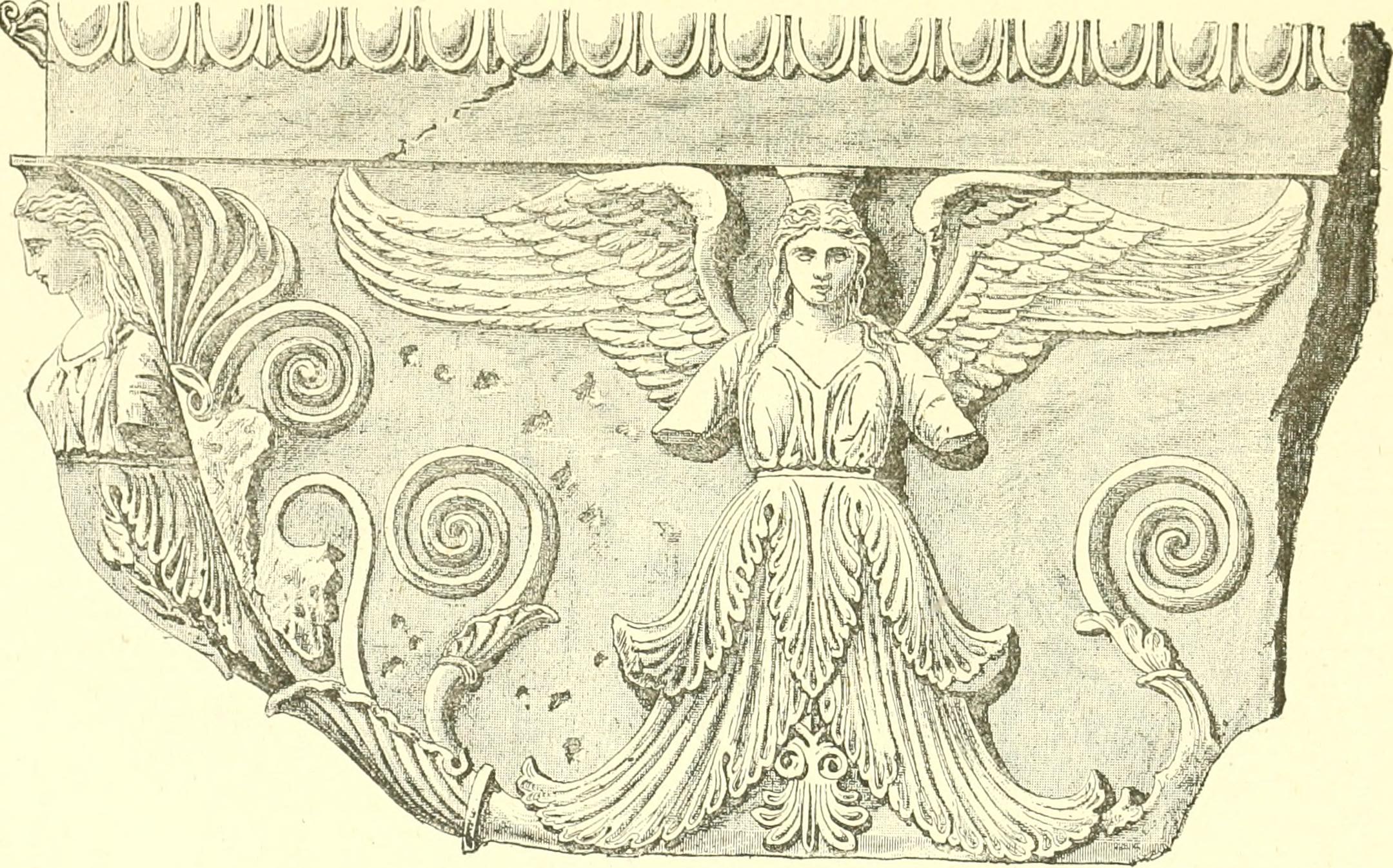

Image source- British Library

[video_ads]

[video_ads2]

You can send your stories/happenings here:info@religionworld.in