Religion & Films: Adi Shankaracharya

Films have undoubtedly been the most influential and ever inspiring medium. They enlighten and inform people about different things in the world. While some take them into the futuristic world, there have been many films globally that have taken us back to our roots to educate about our customs and religions.

This is not just pertained to Indian films, worldwide many filmmakers have used this medium to inform and educate people about different religious aspects or about different Gods that have contributed to religious growth of different communities.

This new weekly column – Religion & Films – will look at how filmmakers have used this most powerful and highly influential medium to talk about their religion or religious gurus. This will also look at the different films that have been successful and have also courted controversy. We also will look at how certain films have been used by sections to spread to the message of religion in their own way.

The series Religion & Films will not look at different films with religious themes in a chronological manner but would pick films from different categories and sections to present the global perspective of films with religious subjects.

Adi Shankaracharya – Sanskrit Film

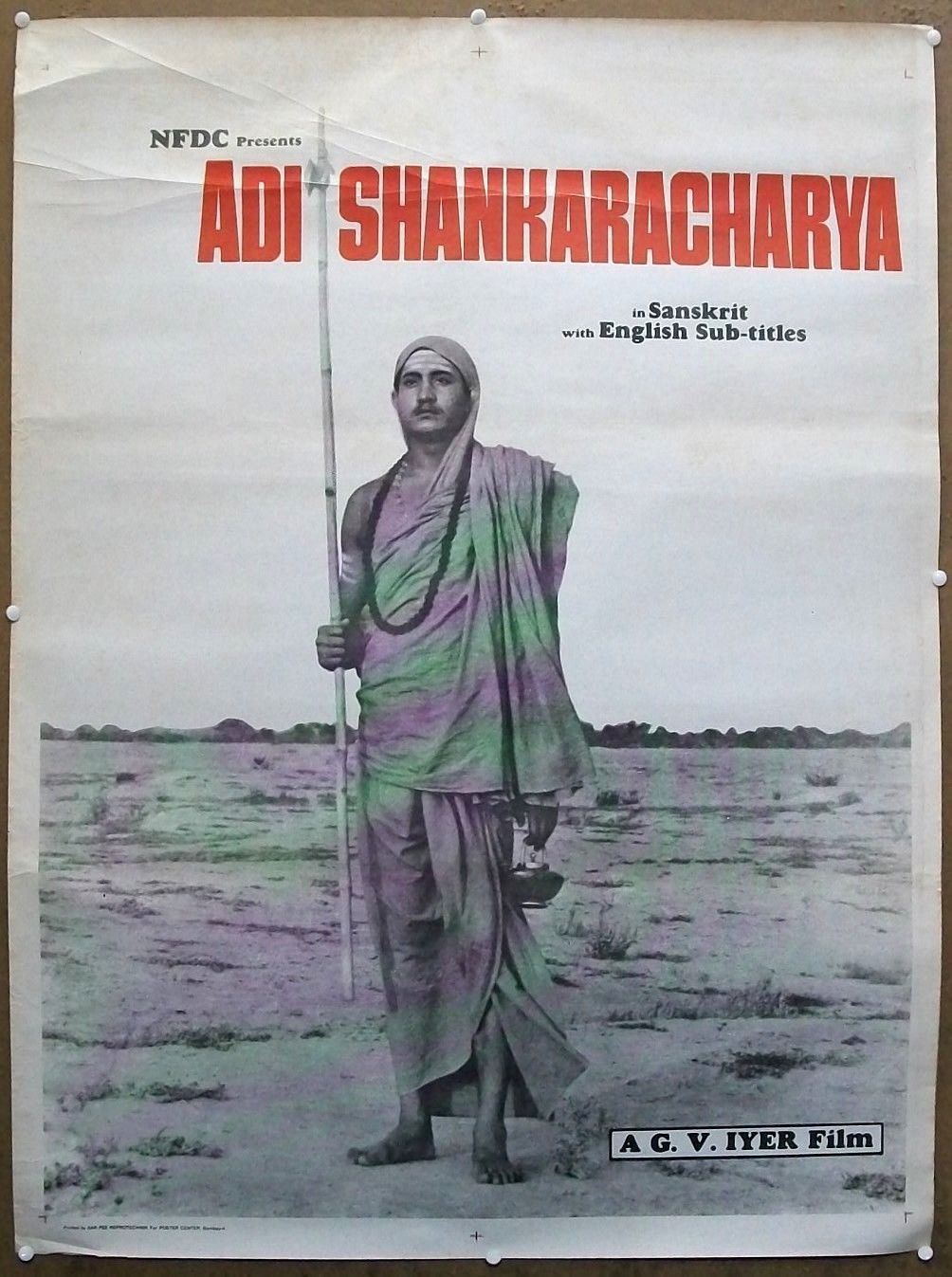

Adi Shankaracharya is India’s first full-fledged film to be made in the Sanskrit language. It is a biopic on ancient Hindu saint Adi Shankaracharya who was instrumental reviving Hinduism and also establishing the four Peethams of Hinduism across the country. This film, which has been produced by National Film Development Corporation, is classic in all respects. The film is not just popular for promoting Hinduism but is very well known for its cinematic presentation.

The life of Adi Shankaracharya has been presented in a manner that is easily understood to everyone. This is a film for spiritually inclined people. The film has the credit of being the first one to be taken in Sanskrit. A language that is thousands of years old, but it has taken so long to make a film in it.

Adi Shankaracharya is born in the state of Kerala, he becomes a monk at a young age and travels north, in search of knowledge and truth. It was a time period when Hindus were giving importance to rituals and forgetting the all prevailing, one God. It was also the time period when Buddhism was on the rise. Shankaracharya forms a new school of thinkers preaching the Adhvaitha philosophy. Through his new philosophy and teachings, he changes the views of many scholars and religious people.

The film has been directed by GV Iyer, renowned filmmaker in Kannada. He is known for his association with legends like BV Karanth. He has been a popular filmmaker and later with Hamsageethe he moved into parallel filmmaking. In 1983 he approached NFDC to make India’s first Sanskrit film and it was Adi Shankaracharya. Interestingly, Iyer didn’t fall into the mythical talks around Adi Shankaracharya’s life and stuck to a simple yet very symbolic presentation of Shankara’s life. And this is the reason the film is regarded as the best representation of the Hindu saint’s life.

The film begins at the time when religion in general and sanatana dharma (Hinduism) in particular was in a state of turmoil. Buddhism had started losing its forte and Hinduism was going in the wrong direction. The big battle Shankara had to fight, was not –as this author assumed to be– with Buddhists, but with the blind practitioners of Vedic rites (mainly the followers of purva-mimamsa). For example, animal sacrifices were stopped, but sacrifices were made of animals made of dough. The Upanishadic realization of the true purport of karma-kaaNDa (in the context of parama purushartha) was lost. No one was concerned about the fundamental aspects of reality and truth. The holy city Varanasi, the city where Annapurna and Vishveshwara reside, the city on the holy banks of the holy Ganges, was echoing with Dukrrinkarane [a grammar rule], rather than shivo aham [I am Shiva], the chant of the unity of individual self with the supreme spirit.

Some Unforgettable Sequences

The identification shlokas of the friends of Shankara are played every time they are in action.

- The Nachiketa play done in Kathakali, the traditional dance form of Kerala.

- Punishment” of the thief by the Brahmin.

- Kumarila: Story of Kumarila, a great scholar of Kashi, who wanted to learn the secrets of Buddhists so that he can defeat them. He achieved his objective of defeating Buddhists. Kumarila laments to Shankara that when the Buddhists pushed him off an abyss, he should have said “Let the eternal Vedas save me” instead of saying, as he said, “If Vedas are eternal, let me be saved”. This resulted in him being saved, but he got blinded in an eye. By the time Shankara meets him, Kumarila had defeated his Buddhist master and is immolating himself because he broke the Buddhist tradition of not respecting the master.

- Hastamalaka: The entire episode of Hastamalaka is very moving. Shankara sees a young boy who acts like a mad person. It is Shankara’s keenness which makes him observe that the boy is laughing at the fish that are living in the water and dying when they land on the bank. The boy is clearly amused at the futileness of the whole existence in this dualistic world. If he is laughing at the highest fear, namely death, he should be staring at the greatest truth. This is what is shown when he is playing and stares at the Sun (a representative of the Brahman) directly. The interplay introduces his parents who are worried about him and explain his situation. The funny part is, they are explaining their own ignorance is misapprehending the boy’s illumination. Shankara asks the boy “who he is”. The boy replies “he is the eternal Atman”. Shankara asks the parents to give the boy to him and gives him the ochre robe.

- The release of Mandana Mishra’s parrot: In Maahismathi, Shankara meets Mandana Mishra of the purva-mimamsa fame. Mandana Mishra has a parrot that recites that Vedic rites are the final authority. The parrot, of course is a symbolism for Mandana Mishra himself. While Shankara and Mandana Mishra are debating, prajnana finds out that the parrot eats only pepper and chooses to remain in a cage. While Shankara and Mandana Mishra are debating, prajnana offers the parrot sweet grapes. The parrot says that it likes the sweet grapes. At the same time, Shankara is gives the winning argument. Prajnana offers the parrot why he wants to remain in a cage, rather than being free. Prajnana says that ants will take many life times to climb a mountain, while a parrot with wings can fly over to the top immediately. Shankara at the same time, asks Mandana Mishra why he chooses to take the slow path of Karma, when renunciation will make him free immediately. Prajnana frees the parrot and at the same time, Mandana Mishra accepts defeat. Shankara takes Mandana Mishra as disciple and names him Sureshwara.

- Kerala Style Vedic recitation, as well as many Upanishadic passages rendered beautifully.

Shankara and his disciples reciting Annapoorna ashtakam are very moving.

The direction of music for the movie was by Manganampalli Balamurali himself, who even sang some songs with his melodious heavenly voice. There are names of other doyens, like Nookala chinna Satyanaraya among others in the initial credits list. The first raaga of the movie, of course, had to be Sankara Bharanam [Adornment of Sankara]. Shankara and his disciples singing Annapoorna astakam was memorable. The background score is by B.V.Karanth, who does a good job.

This film was made in 1983 and won the national awards for “Best Feature Film” – NFDC, “Best Screenplay” – GV Iyer, “Best Cinematography” – Madhu Ambat and “Best Audiography”.